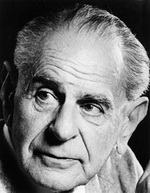

Karl R. Popper

Tahminler ve Çürütmeler. Bölüm 1

Conjectures and Refutations. Chapter 1

Çeviri: Aziz Yardımlı |

KARL R. POPPER

TAHMİNLER VE ÇÜRÜTMELER (1953)

BÖLÜM 1

Bilimsel Bilginin Büyümesi

Peterhouse’da, Cambridge, 1953 Yazında British

Council tarafından düzenlenen ve modern İngiliz felsefesindeki

gelişme ve eğilimler üzerine verilen bir ders; ilk kez ‘‘Philosophy

of Science: a Personal Report’’ olarak C. A. Mace tarafından

düzenlenen British Philosophy in Mid-Century’de yayımlandı,

1957. |

KARL R. POPPER

CONJECTURES AND REFUTATIONS

CHAPTER 1

The Growth of Scientific Knowledge

A lecture given at Peterhouse, Cambridge, in

Summer 1953, as part of a course on developments and trends

in contemporary British philosophy, organized by the British

Council; originally published under the title ‘‘Philosophy

of Science: a Personal Report’’ in British Philosophy in

Mid-Century, ed. C. A. Mace, 1957. |

|

1

BİLİM:

TAHMİNLER VE ÇÜRÜTMELER

Mr. Turnbull kötü sonuçlar öngörmüştü, ... ve bundan böyle kendi peygamberliklerinin doğrulamasını sağlamak için elinden

geleni yapıyor.

— ANTHONY TROLLOPE

Bu derse katılanların listesini aldığım ve

felsefeci meslektaşlara seslenmem istendiğini anladığım

zaman, biraz duruksama ve görüşmelerden sonra belki de beni

en ilgilendiren problemlerden ve en yakından tanışık olduğum

gelişmelerden söz etmemi yeğleyeceğinizi düşündüm. Bu

nedenle daha önce hiç yapmadığım birşeyi yapmaya karar verdim:

size ‘‘Bir kuram ne zaman bilimsel sayılmalıdır?’’

ya da ‘‘Bir kuramın bilimsel karakteri ya da konumu için

bir ölçüt var mıdır?’’ problemi ile ilk kez uğraşmaya

başladığım 1919 sonbaharından bu yana bilim felsefesinde

kendi çalışmam üzerine bir rapor vermek.

|

1

SCIENCE:

CONJECTURES AND REFUTATIONS

Mr. Turnbull had predicted evil consequences,

and as now doing the best in his power to bring about the

verification of his own prophecies.

— ANTHONY

TROLLOPE

WHEN I received the list of participants in

this course and realized that I had been asked to speak to

philosophical colleagues I thought, after some hesitation

and consultation, that you would probably prefer me to speak

about those problems which interest me most, and about those

developments with which I am most intimately acquainted. I

therefore decided to do what I have never done before: to

give you a report on my own work in the philosophy of science,

since the autumn of 1919 when I first began to grapple with

the problem, ‘‘When should a theory be ranked as scientific?’’

or ‘‘Is there a criterion for the scientific character

or status of a theory?’’ |

| O sıralar beni uğraştıran problem ne ‘‘Bir

kuram ne zaman doğrudur?’’ ne de ‘‘Bir kuram

ne zaman kabul edilebilirdir?’’ idi. Problemim bunlardan

ayrıydı. Bilim ve yalancı-bilim arasındaki ayrımı saptamayı

istiyordum; bilimin sık sık yanılgıya düştüğünü ve

yalancı-bilimin pekala gerçekliğe raslayabilecek olduğunu çok iyi biliyordum. |

The problem which troubled me at the time was

neither, ‘‘When is a theory true?’’ nor, ‘‘When is a theory

acceptable?’’ My problem was different. I wished to distinguish

between science and pseudo-science; knowing very well that

science often errs, and that pseudo-science may happen to stumble

on the truth. |

| Hiç kuşkusuz problemime en yaygın olarak kabul

edilen yanıtın bilimin yalancı-bilimden — ya da metafizikten

— görgül yöntemi yoluyla ayırdedildiğini biliyorum

— bir yöntem ki gözlem ya da deneyimden ilerleyerek özsel

olarak tümevarımcıdır. Ama bu beni doyurmuyordu. Tersine, sık sık problemimi gerçekten görgül bir yöntem ile görgül-olmayan ya da giderek

yalancı-görgül bir yöntem (daha açık olarak, gözlem ve deneyime

başvurmasına karşın, gene de bilimsel ölçünlere karşılık vermeyen

bir yöntem) arasında bir ayrım yapma problemi olarak formüle

ettim. Bu yalancı-yöntem gözlem üzerine — horoskoplar

ve yaşamöyküleri üzerine — dayanan heybetli bir görgül kanıt

kütlesi ile astroloji tarafından örneklenebilir. |

I knew, of course, the most widely accepted answer to my problem:

that science is distinguished from pseudo-science — or from

‘‘metaphysics’’ — by its empirical method, which is essentially inductive, proceeding from observation or experiment.

But this did not satisfy me. On the contrary, I often formulated

my problem as one of distinguishing between a genuinely empirical

method and a non-empirical or even a pseudo-empirical method

— that is to say, a method which, although it appeals to observation

and experiment, nevertheless does not come up to a scientific

standards. The latter method may be exemplified by astrology,

with its stupendous mass of empirical evidence based on observation

— on horoscopes and on biographies.

|

| Ama beni problemime götüren şey astroloji örneği

olmadığı için, belki de içinde problemimin doğduğu atmosferi ve

onu uyaran örnekleri kısaca betimlemem iyi olacaktır. Avusturya

İmparatorluğunun çöküşünden sonra Avusturya’da bir devrim olmuştu:

Hava devrimci belgi ve düşünceler ile, ve yeni ve çoğu kez darmadağınık

kuramlar ile doluydu. Beni ilgilendiren kuramlar arasında Einstein’ın

görelilik kuramı hiç kuşkusuz büyük bir ayrımla en önemli olanıydı.

Öteki üçü Marx’ın tarih kuramı, Freud’un ruh-çözümlemesi, ve Alfred Adler’in ‘‘bireysel ruhbilim’’ denilen kuramıydı. |

But as it was not the example of astrology which

led me to my problem I should perhaps briefly describe the atmosphere

in which my problem arose and the examples by which it was stimulated.

After the collapse of the Austrian Empire there had been a revolution

in Austria: the air was full of revolutionary slogans and ideas,

and new and often wild theories. Among the theories which interested

me Einstein’s theory of relativity was no doubt by far the most

important. Three others were Marx’s theory of history, Freud’s

psycho-analysis, and Alfred Adler’s so-called ‘‘individual psychology.’’

|

Bu kuramlar ile, ve özellikle görelilik kuramı

ile ilgili olarak sözü edilen pekçok halksal saçmalık vardı

(bugün bile sürdüğü gibi), ama beni bu kuramı incelemeye götüren

kişiler konusunda talihliydim. Tümümüz — ait olduğum küçük öğrenciler

çevresi — Eddington’un 1919’da Einstein’ın yerçekimi kuramının

ilk önemli doğrulamasını getiren güneş tutulması gözlemlerinden

heyecana kapılmıştık. Bu bizim için büyük bir deneyimdi ve düşünsel

gelişimim üzerinde kalıcı bir etki bıraktı.

|

There was a lot of popular nonsense talked about

these theories, and especially about relativity (as still happens

even today), but I was fortunate in those who introduced me

to the study of this theory. We all — the small circle of students

to which I belonged — where thrilled with the result of Eddington’s

eclipse observations which in 1919 brought the first important

confirmation of Einstein’s theory of gravitation. It was a great

experience for us, and one which had a lasting influence on

my intellectual development. |

| Sözünü ettiğim öteki üç kuram da o sıralar öğrenciler

arasında yaygın olarak tartışılıyordu. Alfred Adler ile kişisel

ilişkim olmuş, ve üstelik Viyana’da toplumsal kılavuzluk klinikleri

kurduğu işçi mahallelerinde çocuklar ve gençler arasında toplumsal

çalışmasında onunla işbirliği yapmıştım. |

The three other theories I have mentioned were

also widely discussed among students at that time. I myself

happened to come into personal contact with Alfred Adler, and

even to co-operate with him in his social work among the children

and young people in the working-class districts of Vienna where

he had established social guidance clinics. |

| 1919 yazı sırasında bu üç kuramdan giderek artan

bir doyumsuzluk duymaya başladım — Marxist tarih kuramı, ruh-çözümleme,

ve bireysel ruhbilim; ve bilimsellik savlarından kuşkulanmaya

başladım. Problemim belki de ilkin ‘‘Marxizm, ruh-çözümleme, ve

bireysel ruhbilimde ters giden nedir?’’ gibi yalın bir biçimdeydi.

Bunlar niçin fiziksel kuramlardan, Newton’ın kuramından, ve

özellikle görelilik kuramından böylesine ayrıdır? |

It was during the summer of 1919 that I began

to feel more and more dissatisfied with these three theories

— the Marxist theory of history, psycho-analysis, and individual

psychology; and I began to feel dubious about their claims to

scientific status. My problem perhaps first took the simple

form, ‘‘What is wrong with Marxism, psycho-analysis, and individual

psychology? Why are they so different from physical theories,

from Newton’s theory, and especially from the theory of relativity?’’ |

| Bu zıtlığı açıkça göstermek için belirtmem gerek

ki o sıralar çok azımız Einstein’ın yerçekimi kuramının doğruluğuna inandığını söyleyecekti. Bu beni uğraştıran şeyin öteki üç kuramın doğruluklarından kuşkulanmam değil, ama başka birşey

olduğunu gösterir. Gene de yalnızca bu matematiksel fiziğin

toplumbilimsel ya da ruhbilimsel kuram tipinden daha sağın olduğunu sezmem de değildi. Böylece beni endişelendiren şey

en azından o sıralar ne doğruluk problemi, ne de sağınlık ya da

ölçülebilirlik problemi idi. Bu dahaçok öteki üç kuramın, gerçi

birer bilim olarak ortaya çıksalar da, gerçekte bilimden çok

ilkel mitler ile ortaklık taşımaları, astronomiden çok astorolijiyi

andırmaları idi. |

To make this contrast clear I should explain that

few of us at the time would have said that we believed in the truth of Einstein’s theory of gravitation. This shows

that it was not my doubting the truth of those other

three theories which bothered me, but something else. Yet neither

was it that I merely felt mathematical physics to be more exact that the sociological or psychological type of theory. Thus

what worried me was neither the problem of truth, at that stage

at least, nor the problem of exactness or measurability. It

was rather that I felt that these other three theories, though

posing as science, had in fact more in common with primitive

myths that with science; that they resembled astrology rather

than astronomy. |

| Marx, Freud ve Adler’in hayranları olan arkadaşlarımın

bu kuramlara ortak bir dizi noktadan, özellikle görünürdeki açıklayıcı güçlerinden etkilendiklerini buldum. Bu kuramlar

aşağı yukarı ilgili oldukları alanların içersinde yer alan herşeyi

açıklayabilmeye yetenekli görünüyorlardı. Herhangi birini incelemek

düşünsel bir inanç değişiminin ya da bir tanrısal bildirişin

etkisini yaratıyor, gözlerinizi henüz onlarla tanışmamış olanlardan

gizlenen yeni bir gerçekliğe açıyor görünüyorlardı. Bir kez

böylece gözleriniz açıldıktan sonra her yerde doğrulayıcı örnekler

görmeye başlıyordunuz: dünya kuramın doğrulamaları ile

doluydu. Olan her şey her zaman onu doğruluyordu. Böylece kuramın

doğruluğu apaçık ortada görünüyordu; ve inanmayanlar hiç kuşkusuz

bu belirtik gerçeği görmek istemeyen kişilerdi, ve bunu görmeyi

ya sınıf çıkarlarına karşı olduğu için, ya da henüz çözümlenmemiş

ve sağaltım için haykıran baskıları nedeniyle yadsıyorlardı. |

I found that those of my friends who were admirers

of Marx, Freud, and Adler, were impressed by a number of points

common to these theories, and especially by their apparent explanatory

power. These theories appeared to be able to explain practically

everything that happened within the fields to which they referred.

The study of any of them seemed to have the effect of an intellectual

conversion or revelation, opening your eyes to a new truth hidden

from those not yet initiated. Once your eyes were thus opened

you saw confirming instances everywhere: the world was full

of verifications of the theory. Whatever happened always

confirmed it. Thus its truth appeared manifest; and unbelievers

were clearly people who did not want to see the manifest truth;

who refused to see it, either because it was against their class

interest, or because of their repressions which were still ‘‘un-analysed’’

and crying aloud for treatment.

|

Bu durumdaki en tipik öğe bana doğrulamaların,

söz konusu kuramları ‘‘doğrulayan’’ gözlemlerin dinmek bilmez

akışı olarak görünüyordu; ve bu nokta bu kuramların yandaşları

tarafından sürekli olarak vurgulanıyordu. Bir Marxist bir gazeteyi

her sayfasında onun tarih yorumu için doğrulayıcı kanıt bulmaksızın

açamazdı; yalnızca haberlerde değil ama sunuluşlarında da —

ki gazetenin sınıf eğilimin ele veriyordu — ve özellikle gazetenin

söylemediklerinde. Freudcu çözümlemeci kuramlarının ‘‘klinik

gözlemleri’’ tarafından sürekli olarak doğrulandığını vurguluyordu.

Adlere’e gelince, kişisel bir deneyimden çok fazla etkilendim.

1919’da bir keresinde ona bana özellikle kuramına uygun görünmeyen

bir durumu bildirdim, ama kendisi bunu aşağılık duyguları kuramının

terimlerinde çözümlemede hiçbir güçlük çekmedi, üstelik daha çocuğu

bile görmemişken. Biraz şaşırarak ona nasıl böyle emin olabildiğini

sordum. ‘‘Bin kez edindiğim deneyimler nedeniyle’’ yanıtını

verdi; bunun üzerine şunu söylemenin önüne geçemedim: ‘‘Ve bu

yeni örnekle, sanırım, deneyiminiz bin-bir oldu.’’

|

The most characteristic element in this situation

seemed to me the incessant stream of confirmations, of observations

which ‘‘verified’’ the theories in question; and this point

was constantly emphasized by their adherents. A Marxist could

not open a newspaper without finding on every page confirming

evidence for his interpretation of history; not only in the

news, but also in its presentation — which revealed the class

bias of the paper — and especially of course in what the paper

did not say. The Freudian analysts emphasized that their

theories were constantly verified by their ‘‘clinical observations’’.

As for Adler, I was much impressed by a personal experience.

Once, in 1919, I reported to him a case which to me did not

seem particularly Adlerian, but which he found no difficulty

in analysing in terms of his theory of inferiority feelings,

although he had not even seen the child. Slightly shocked, I

asked him how he could be so sure. ‘‘Because of my thousandfold

experience,’’ he replied; whereupon I could not help saying:

And with this new case, I suppose, your experience has become

thousand-and-one-fold.’’ |

Kafamda olan şey önceki gözlemlerinin bu yeni

gözlemden çok daha sağlam olmuş olmayabileceği, her birinin

kendi payına ‘‘önceki deneyim’’in ışığında yorumlanmış olduğu,

ve aynı zamanda ek doğrulama olarak kabul edildiği idi. Neyi

doğruladı, diye sordum kendime. Bir durumun kuramın ışığında

yorumlanabilecek olduğundan daha çoğunu değil. Ama bunun çok

az önemi olduğunu düşündüm, çünkü tasarlanabilir her durum Adler’in

ya da eşit ölçüde Freud’un kuramının ışığında yorumlanabilirdi.

Bunu insan davranışının çok ayrı iki örneği ile açıklayabilirim:

bir çocuğu boğma niyetiyle suya iten bir adam örneği; ve çocuğu

kurtarma girişiminde yaşamından özveride bulunan bir adam örneği.

Bu iki durumdan her biri Freudcu ve Adlerci terimlerde eşit

kolaylıkla açıklanabilir. Freud’a göre ilk adam baskı (diyelim

ki, Ödipus karmaşasındaki bir bileşenin baskısı) altında iken,

ikincisi ise yüceltmeyi başarmıştı. Adler’e göre birincisi (belki

de kendine bir suç işlemeyi göze alabileceğini tanıtlama gereksinimini

üreten) aşağılık duygularının etkisi altında iken, (gereksinimi

kendine çocuğu kurtarmayı göze aldığını tanıtlamak olan) ikincisi

de yine aynı duyguların etkisi altındaydı. Her iki kuramın da

terimlerinde yorumlanamayacak hiçbir insan davranışı düşünemiyorum.

Tam olarak bu olgu — her zaman uymaları, her zaman doğrulanmaları

— idi ki hayranlarının gözünde bu kuramlardan yana en güçlü

uslamlamayı oluşturuyordu. Yavaş yavaş bu görünürdeki gücün

gerçekte zayıflıkları olduğunu anlamaya başlıyordum.

|

What I had in mind was that his previous observations

may not have been much sounder than this new one; that each

in its turn had been interpreted in the light of ‘‘previous

experience’’, and at the same time counted as additional confirmation.

What, I asked myself, did it confirm? No more than that a case

could be interpreted in the light of the theory. But this meant

very little, I reflected, since every conceivable case could

be interpreted in the light of Adler’s theory, or equally of

Freud’s. I may illustrate this by two different examples of

human behaviour: that of a man who pushes a child into the water

with the intention of drowning it; and that of a man who sacrifices

his life in attempt to save the child. Each of these two cases

can be explained with equal ease in Freudian and in Adlerian

terms. According to Freud the first man suffered from repression

(say, of some component of his Oedipus complex), while the second

man had achieved sublimation. According to Adler the first man

suffered from feelings of inferiority (producing perhaps the

need to prove to himself that he dared to commit some crime),

and so did the second man (whose need was to prove to himself

that he dared to rescue the child). I could not think of any

human behaviour which could not be interpreted in terms of either

theory. It was precisely this fact — that they always fitted,

that they were always confirmed — which in the eyes of their

admirers constituted the strongest argument in favour of these

theories. It began to dawn on me that this apparent strength

was in fact their weakness. |

Einstein’ın kuramı açısından durum çarpıcı bir

biçimde ayrıydı. Tek bir tipik durumu alalım — Einstein’ın tam

o sıralar Eddingston’ın araştırmasının bulguları tarafından

doğrulanan öngörüsünü. Einstein’ın çekim kuramı ışığın,

tam olarak özdeksel cisimlerin çekilmesi gibi, ağır cisimler

(örneğin güneş gibi) tarafından çekilmesi gerektiği sonucuna

götürmüştü.Bir sonuç olarak görünürdeki konumu güneşe yakın

olan uzak bir durağan yıldızdan gelen ışığın dünyaya yıldızın

güneşten biraz uzağa kaymış gibi görüneceği bir yönde ulaşacağı,

ya da başka bir deyişle, güneşe yakın yıldızların sanki güneşten

ve birbirlerinden biraz uzaklaşmış gibi görünecekleri hesaplanabilirdi.

Bu normal olarak gözlenemeyen bir şeydir çünkü böyle yıldızlar

güneşin aşırı parlaklığı tarafından gündüzleri görülmez kılınırlar;

ama bir güneş tutulması sırasında fotoğraflarını almak olanaklıdır.

Eğer aynı yıldızlar öbeğinin gece fotoğrafı alınırsa uzaklık

iki fotoğraf üzerindeki ölçülebilir ve öngörülen etki yoklanabilir.

|

With Einstein’s theory the situation was strikingly

different. Take one typical instance — Einstein’s prediction,

just then confirmed by the findings of Eddington’s expedition.

Einstein’s gravitational theory had led to the result that light

must be attracted by heavy bodies (such as the sun), precisely

as material bodies were attracted. As a consequence it could

be calculated that light from a distant fixed star whose apparent

position was close to the sun would reach the earth from such

a direction that the star would seem to be slightly shifted

away from the sun; or, in other words, that stars close to the

sun would look as if they had moved a little away from the sun,

and from one another. This is a thing which cannot normally

be observed since such stars are render invisible in daytime

by the sun’s overwhelming brightness; but during an eclipse

it is possible to take photographs of them. If the same constellation

is photographed at night one can measure the distance on the

two photographs, and check the predicted effect. |

Şimdi bu durumda etkileyici olan bu tür bir öngörünün içerdiği risktir. Eğer gözlem öngörülen etkinin kesinlikle bulunmadığını

gösterirse, o zaman kuram doğrudan doğruya çürütülmüş olur.

Kuram gözlemin belli olanaklı sonuçlarıyla bağdaşmazdır — gerçekte, Einstein’dan önce herkesin beklemiş olacağı

sonuçlarla.1 Bu daha önce betimlemiş olduğum durumdan

bütünüyle ayrıdır, çünkü söz konusu kuramlar birbirinden en

uzak insan davranışları ile bağdaşabilir olduklarını gösteriyorlardı,

öyle ki bu kuramların bir doğrulaması olarak ileri sürülemeyecek

herhangi bir insan davranışını betimlemek hemen hemen olanaksızdı.

1Bu biraz aşırı bir yalınlaştırmadır, çünkü Einstein

etkisinin yaklaşık olarak yarısı klasik kuramdan türetilebilir,

yeter ki bir balistik ışık kuramı varsayalım. |

Now the impressive thing about this case is the risk involved

in a prediction of this kind. If observation shows that the

predicted effect is definitely absent, then the theory is

simply refuted. The theory is incompatible with certain

possible results of observation — in fact with results

which everybody before Einstein would have expected.1 This is quite different from the situation I have previously

described, when it turned out that the theories in question

were compatible with the most divergent human behaviour, so

that it was practically impossible to describe any human behaviour

that might not be claimed to be a verification of these theories.

1This is a slight oversimplification, for about

half of the Einstein effect may be derived from the classical

theory, provided we assume a ballistic theory of light. |

Bu irdelemeler beni 1919-20 kışında şimdi yeniden şöyle formüle

edebileceğim vargılara götürdü.

(1) Hemen hemen her kuram için doğrulamalar ya da gerçeklemeler

elde etmek kolaydır — eğer doğrulamalar ararsak.

(2) Doğrulamalar ancak riskli öngörülerin sonuçları

iseler kabul edilmelidir; başka bir deyişle, eğer, söz konusu

kuram tarafından aydınlatılmamış olarak, kuram ile bağdaşmaz

ve kuramı çürütecek olan bir olayı beklememiz gerekmişse.

(3) Her ‘‘iyi’’ bilimsel kuram bir yasaklamadır: belli şeylerin

olmasını yasaklar. Bir kuram ne denli yasaklayıcı ise o denli

iyidir.

(4) Tasarlanabilir hiçbir olay tarafından çürütülemeyen bir

kuram bilimsel değildir. Çürütülemezlik bir kuram için erdem

(insanların sık sık düşündükleri gibi) değil, ama bir kusurdur.

(5) Bir kuramın her gerçek sınaması onu yanlışlama

ya da çürütme girişimidir. Sınanabilirlik yanlışlanabilirliktir;

ama sınanabilirliğin dereceleri vardır: kimi kuramlar başkalarından

daha sınanabilirdir, çürütülmeye daha açık dururlar; bir bakıma

daha büyük riskler alırlar.

(6) Doğrulayıcı kanıt kuramın gerçek bir sınamasının sonucu

olması dışında geçerli olmamalıdır; ve bu onun kuramı

yanlışlamak için ciddi ama başarısız bir girişim olarak sunulabilmesi

demektir. (Şimdi böyle durumlarda ‘‘onaylayıcı kanıt’’tan

söz ediyorum.)

(7) Kimi gerçekten sınanabilir kuramlar, yanlış oldukları

bulduğu zaman, henüz hayranları tarafından savunulmayı sürdürürler

— örneğin özel bir yardımcı sayıltı getirerek, ya da kuramı

özel olarak çürütülmeden kaçabileceği bir yolda yeniden-yorumlayarak.

Böyle bir yordam her zaman olanaklıdır, ama kuramı çürütülmekten

ancak bilimsel konumunu yok ederek, ya da en azından alçaltarak

kurtarır. (Daha sonra böyle bir kurtarma işlemini bir ‘‘uylaşımcı

büküm’’ ya da bir ‘‘uylaşımcı manevra’’ olarak

betimledim.)

Tüm bunlar bir kuramın bilimsel konumunun ölçütü onun

yanlışlanabilirliği, ya da çürütülebilirliği, ya da sınanabilirliğidir denerek toparlanabilir.

|

These considerations led me in the winter of 1919-20 to conclusions

which I may now reformulate as follows.

(1) It is easy to obtain confirmations, or verifications,

for nearly every theory — if we look for confirmations.

(2) Confirmations should count only if they are the result

of risky predictions; that is to say, if, unenlightened

by the theory in question, we should have expected an event

which was incompatible with the theory — an event which would

have refuted the theory.

(3) Every ‘‘good’’ scientific theory is a prohibition: it

forbids certain things to happen. The more a theory forbids,

the better it is.

(4) A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event

is non-scientific. Irrefutability is not a virtue of a theory

(as people often think) but a vice.

(5) Every genuine test of a theory is an attempt to

falsify it, or to refute it. Testability is falsifiability;

but there are degrees of testability; some theorise are more

testable, more exposed to refutation, than others; they take,

as it were, greater risks.

(6) Confirming evidence should not count except when it

is the result of a genuine test of the theory; and this

means that it can be presented as a serious but unsuccessful

attempt to falsify the theory. (I now speak in such cases

of ‘‘corroborating evidence’’.)

(7) Some genuinely testable theories, when found to be false,

are still upheld by their admirers — for example by introducing ad hoc some auxiliary assumption, or by re-interpreting

the theory ad hoc in such a way that it escapes refutation.

Such a procedure is always possible, but it rescues the theory

from refutation only as the price of destroying, or at least

lowering, its scientific status. (I later described such a

rescuing operation as a ‘‘conventionalist twist’’ or

a ‘‘conventionalist stratagem’’.)

One can sum up all this by saying that the criterion of

the scientific status of a theory is its falsifiability, or

refutability, or testability. |

II

Belki de bunu şimdiye dek sözü edilen çeşitli kuramların yardımıyla

örnekleyebilirim. Einstein’ın yerçekimi kuramı açıktır ki yanlışlanabilirlik

ölçütüne yanıt veriyordu. O zamanki ölçüm araçlarımız sınamaları

tam bir güvenle bildirmemize izin vermemiş olsaydı bile, açıktır

ki kuramı çürütmenin bir olanağı vardı.

|

II

I may perhaps exemplify this with the help of the various

theories so far mentioned. Einstein’s theory of gravitation

clearly satisfied the criterion of falsifiability. Even if

our measuring instruments at the time did not allow us to

pronounce on the result of the tests with complete assurance,

there was clearly a possibility of refuting the theory. |

| Astroloji sınavı geçemedi. Astrologlar doğrulayıcı

kanıt olduğuna inandıkları şey tarafından büyük ölçüde etkilendiler

ve aldatıldılar — öyle bir düzeyde ki yandaş olmayan hiçbir

kanıt tarafından etkilenmediler. Dahası, yorumlarını ve peygamberce

öngörülerini yeterince bulanıklaştırmakla, kuram ve peygamberliklerin

daha sağın olmuş olması durumunda kuramın bir çürütülmesi olabilecek

herşeyi geçiştirebildiler. Yanlışlamadan kaçabilmek için kuramlarının

sınanabilirliğini yokettiler. Tipik bir falcının hilesi şeyler

üzerine boşa çıkamayacak denli ve böylece çürütülemeyecek denli

bulanık öngörülerde bulunmaktır. |

Astrology did not pass the test. Astrologers were

greatly impressed, and misled, by what they believed to be confirming

evidence — so much so that they were quite unimpressed by any

unfavourable evidence. Moreover, by making their interpretations

and prophecies sufficiently vague they were able to explain

away anything that might have been a refutation of the theory

had the theory and the prophecies been more precise. In order

to escape falsification they destroyed the testability of their

theory. It is a typical soothsayer’s trick to predict things

so vaguely that the predictions can hardly fail: that they become

irrefutable. |

Marxist tarih kuramı, kimi kurucu ve izleyicilerinin ciddi

çabalarına karşın, en sonunda bu bilicilik uygulamasını kabul

etti. Erken formülasyonlarından kimilerinde (örneğin Marx’ın

‘‘gelen toplumsal devrim’’in karakterini çözümlemesinde) öngörüleri sınanabilirdi,

ve gerçekten de yanlışlandılar.2 Gene de, çürütmeleri

kabul etmek yerine, Marx’ın izleyicileri hem kuramı hem de

kanıtı onları bağdaştırmak için yeniden-yorumladılar. Bu yolda

kuramı çürütülmekten kurtardılar; ama bunu onu çürütülemez

kılan bir aygıtı benimseme pahasına yaptılar. Böylece kurama

bir ‘‘uylaşımcı büküm’’ verdiler; ve bu manevra ile onun üzerinde

çok diretilen bilimsellik savını yokettiler.

2Bkz. Örneğin Open Society and Its Enemies başlıklı çalışmam, Bölüm 15, Kesim iii, ve notlar 13-14. |

The Marxist theory of history, in spite of the serious efforts

of some of its founders and followers, ultimately adopted

this soothsaying practice. In some of its earlier formulations

(for example in Marx’s analysis of the character of the ‘‘coming

social revolution’’) their predictions were testable, and

in fact falsified.2 Yet instead of accepting the

refutations the followers of Marx re-interpreted both the

theory and the evidence in order to make the agree. In this

way they rescued the theory from refutation; but they did

so at the price of adopting a device which made it irrefutable.

They thus gave a ‘‘conventionalist twist’’ to the theory;

and by this stratagem they destroyed its much advertised claim

to scientific status.

2See, for example, my Open Society and Its Enemies, ch. 15, section iii, and notes 13-14. |

İki ruh-çözümsel kuram da ayrı birer sınıfta idi. Ne olursa

olsun sınanamaz, çürütülemez idiler. Onlarla

çelişkiye düşebilecek tasarlanabilir hiçbir insan davranışı

yoktu. Bu demek değildir ki Freud ve Adler belli şeyleri doğru

olarak görmüyorlardı: Söylediklerinin çoğunun oldukça önemli

olduğundan ve bir gün sınanabilir bir ruhbilimde yerlerini

alabileceğinden kişisel olarak kuşku duymuyorum. Ama demektir

ki çözümlemecilerin safça kuramlarını doğruladığına inandıkları

o ‘‘klinik gözlemler’’ bunu astrologların kendi kılgılarında

buldukları gündelik doğrulamalardan daha öte güçlü bir biçimde

yerine getiremez.3 Ve Freud’un Ben, Üst-ben ve O epiğine gelince, onun için Homer’in

toplu Olimpus öyküleri için olduğundan daha güçlü bir bilimsel

konum savında bulunulamaz. Bu kuramlar kimi olguları betimler,

ama mitlerin tarzında. Çok ilginç ruhbilimsel öneriler kapsarlar,

ama sınanabilir bir biçimde değil.

3‘‘Klinik gözlemler,’’ tüm başka gözlemler gibi, kuramların ışığı altındaki yorumlardır (bkz. aşağıda

kesim IV vs.); ve salt bu nedenle ışığında yorumlandıkları

kuramları destekliyor görünme eğilimindedirler. Ama gerçek

destek ancak (‘‘girişilen çürütmeler’’ yoluyla) sınamalar

olarak üstlenilen gözlemlerden elde edilebilir; ve bu amaçla çürütme ölçütü önceden ortaya koyulmalıdır: hangi gözlenebilir

durumların — eğer edimsel olarak gözleniyorlarsa — kuramın

çürütülmesi demek olduğunda anlaşılmalıdır. Ama ne tür klinik

karşılıklar çözümlemeciyi doyuracak bir yolda yalnızca tikel

bir çözümsel tanıyı değil ama ruh-çözümlemenin kendisini çürütürler?

Ve böyle ölçütler çözümlemeciler tarafından hiç tartışılmış

ve üzerlerinde anlaşılmış mıdır? Tersine, böyle ölçütler üzerinde

anlaşmayı olanaksızlaştırmasa da güçleştirecek olan ‘‘ikircim’’

gibi bütün bir çözümsel kavramlar ailesi yok mudur (‘‘ikircim’’

diye birşeyin olmadığını demek istemiyorum)? Dahası, (bilinçli

ve bilinçsiz) beklentilerin ve çözümlemeci tarafından savunulan

kuramların hastanın ‘‘klinik karşılıkları’’nı etkilediği düzeyi

ilgilendiren soruyu araştırmada ne denli ilerleme yapılmıştır?

(Hastaya yorumlar önererek onu bilinçli olarak etkileme vb.

gibi girişimler bir yana.) Yıllar önce bir kuramın ya da beklentinin

ya da öngörünün betimlediği ya da öngördüğü olay üzerindeki etkisini betimlemek için ‘‘Oedipus etkisi’’ terimini

getirdim: anımsanacaktır ki Oedipus’un baba-öldürmesine götüren

nedensel zincir bilicinin bu olayı öngörüsü tarafından başlatıldı.

Bu böyle mitlerin tipik ve yineleyen bir temasıdır, ama belki

de raslantısal olmayarak çözümlemecinin ilgisini çekmeyi başaramamış

görünen bir temadır. (Çözümlemeci tarafından telkin edilen

doğrulayıcı düşler kuramını Freud örneğin Gesammelte Schriften’de,

III, 1925, tartışır ve orada s. 314’te şunları söyler: ‘‘Eğer

biri bir çözümlemede kullanılabilecek düşlerin çoğunun ...

kökenlerini [çözümlemeciden gelen] telkine borçlu olduğunu

ileri sürerse, o zaman çözümleme kuramının bakış açısından

hiçbir karşıçıkış getirilemez.’’ Ve şaşırtıcı bir biçimde,

‘‘Gene de bu olguda sonuçlarımızın güvenilebilirliğini azaltacak

hiçbirşey yoktur’’ diye ekler.) |

The two psycho-analytic theories were in a different class.

They were simply non-testable, irrefutable. There was no conceivable

human behaviour which could contradict them. This does not

mean that Freud and Adler were not seeing certain things correctly:

I personally do not doubt that much of what they say is of

considerable importance, and may well play its part one day

in a psychological science which is testable. But it does

mean that those ‘‘clinical observations’’ which analysts naively

believe confirm their theory cannot do this any more than

the daily confirmations which astrologers find in their practice.3 And as for Freud’s epic of the Ego, the Super-ego, and the

Id, no substantially stronger claim to scientific status can

be made for it than for Homer’s collected stories from Olympus.

These theories describe some facts, bun in the manner of myths.

They contain most interesting psychological suggestions, but

not in a testable form.

3‘‘Clinical observations,’’ like all other observations,

are interpretations in the light of theories (see below,

sections iv ff.); and for this reason alone they are apt to

seem to support those theories in the light of which they

were interpreted. But real support can be obtained only from

observations undertaken as tests (by ‘‘attempted refutations’’);

and for this purpose criteria of refutation have to

be laid down beforehand: it must be agreed which observable

situations, if actually observed, mean that the theory is

refuted. But what kind of clinical responses would refute

to the satisfaction of the analyst not merely a particular

analytic diagnosis but psycho-analysis itself? And have such

criteria ever been discussed or agreed upon by analysts? Is

there not, on the contrary, a whole family of analytic concepts,

such as ambivalence’’ (I do not suggest that there is no such

thing as ambivalence), which would make it difficult, if not

impossible, to agree upon such criteria? Moreover how much

headway has been made in investigating the question of the

extent to which the (conscious or unconscious) expectations

and theories held by the analyst influence the ‘‘clinical

responses’’ of the patient? (To say nothing about the conscious

attempts to influence the patient by proposing interpretations

to him, etc.) Years ago I introduced the term ‘‘Oedipus

effect’’ to describe the influence of a theory or expectation

or prediction upon the event which it predicts or describes:

it will be remembered that the causal chain leading to Oedipus’

parricide was started by the oracle’s prediction of this event.

This is a characteristic and recurrent theme of such myths,

but one which seems to have failed to attract the interest

of the analysts, perhaps not accidentally. (The problem of

confirmatory dreams suggested by the analyst is discussed

by Freud, for example in Gesammelte Schriften, III,

1925, where he says on p. 314: ‘‘If anybody asserts that most

of the dreams which can be utilized in an analysis. ... owe

their origin to [the analyst’s] suggestion, than no objection

can be made from the point of view of analytic theory. Yet

there is nothing in this fact,’’ he surprisingly adds, ‘‘which

would detract from the reliability of our results.’’) |

Aynı zamanda böyle mitlerin geliştirilebilir ve sınanabilir

olduklarını anladım; tarihsel olarak konuşursak, tüm — ya

da hemen hemen tüm — bilimsel kuramlar mitlerden doğarlar,

ve bir mit bilimsel kuramlar için önemli öncelemeler kapsayabilir.

Örnekler Empedokles’in yanılma ve sınama yoluyla evrim kuramı,

ya da Parmenides’in değişmeyen blok evrenidir — bir evren

ki içinde hiçbirşey yer almaz ve eğer bir başka boyut eklersek

Einstein’ın blok evreni olur (ki bunda da hiçbirşey yer almaz,

çünkü herşey, dört-boyutlu olarak konuşursak, başlangıçtan

belirlenmiş ve ortaya koyulmuştur). Böylece eğer bir kuramın

bilimsel olmadığı ya da (deyim yerindeyse) ‘‘metafiziksel’’

olduğu bulunacak olursa, böylelikle önemsiz ya da imlemsiz

ya da ‘‘anlamsız’’ ya da ‘‘saçma’’ olduğunun bulunmadığını

anladım.4 Ama bilimsel anlamda görgül kanıt tarafından

desteklendiğini ileri süremez — gerçi, belli bir ortaya çıkış

anlamında, ‘‘gözlem sonucu’’ olsabilse de.

4Günümüzde tipik bir yalancı-bilim olan astroloji

olgusu bu noktayı örnekleyebilir. Astrololji Aristotelesciler

ve başka ussalcılar tarafından Newton’un gününe dek yanlış

nedenle saldırıya uğradı — gezegenlerin dünyasal (‘‘ay-altı’’)

olaylar üzerinde bir ‘‘etkileri’’ olduğu yolundaki şimdi kabul

edilen önesürüm nedeniyle. Gerçekte Newton’un çekim kuramı,

ve özellikle dalgalar üzerine ay kuramı, tarihsel olarak konuşursak,

astrolojik ilmin bir türevi idi. Öyle görünür ki Newton örneğin

‘‘grip’’ [‘‘influenza’’] salgınlarının yıldız ‘‘etkisi’’ne

[‘‘influence’’] bağlı olduğu kuramı ile aynı soydan gelen

bir kuramı benimseme konusunda çok isteksizdi. Ve Galileo,

hiç kuşkusuz aynı nedenle, dalgalar üzerine ay kuramını edimsel

olarak yadsıdı; ve Kepler’e ilişkin kuşkuları astrolojiye

ilişkin kuşkuları ile kolayca açıklanabilir. |

At the same time I realized that such myths may be developed,

and become testable; that historically speaking all—or very

nearly all — scientific theories originate from myths, and

that a myth may contain important anticipations of scientific

theories. Examples are Empedocles’ theory of evolution by

trial and error, or Parmenides’ myth of the unchanging block

universe in which nothing ever happens and which, if we add

another dimension, becomes Einstein’s block universe (in which,

too, nothing ever happens, since everything is, four-dimensionally

speaking, determined and laid down from the beginning). I

thus felt that if a theory is found to be non-scientific,

or ‘‘metaphysical’’ (as we might say), it is not thereby found

to be unimportant, or insignificant, or ‘‘meaningless,’’ or

‘‘nonsensical.’’4 But it cannot claim to be backed

by empirical evidence in the scientific sense — although it

may easily be, in some genetic sense, the ‘‘result of observation.’’

4The case of astrology, nowadays a typical

pseudo-science, may illustrate this point. It was attacked,

by Aristotelians and other rationalists, down to Newton’s

day, for the wrong reason—for its now accepted assertion that

the planets had an ‘‘influence’’ upon terrestrial (‘‘sublunar’’)

events. In fact Newton’s theory of gravity, and especially

the lunar theory of the tides, was historically speaking an

offspring of astrological lore. Newton, it seems, was most

reluctant to adopt a theory which came from the same stable

as for example the theory that ‘‘influenza’’ epidemics are

due to an astral ‘‘influence.’’ And Galileo, no doubt for

the same reason, actually rejected the lunar theory of the

tides; and his misgivings about Kepler may easily be explained

by his misgivings about astrology.

|

| (Bu ön-bilimsel ya da yalancı-bilimsel karakterde başka

birçok kuram daha vardı, ve bunlardan kimileri ne yazık ki Marxist

tarih yorumu denli etkiliydi; örneğin, ırkçı tarih yorumu —

tanrısal bildirişler gibi zayıf kafalar üzerinde çalışan etkileyici

ve herşeyi-açıklayıcı kuramlardan bir başkası.) |

(There were a great many other theories of this

pre-scientific or pseudo-scientific character, some of them,

unfortunately, as influential as the Marxist interpretation

of history; for example, the racialist interpretation of history

— another of those impressive and all-explanatory theories which

act upon weak minds like revelations.) |

Böylece yanlışlanabilirlik ölçütünü önererek çözmeye

çalıştığım problem ne bir anlamlılık ya da imlemlilik problemi,

ne de doğruluk ya da kabul edilebilirlik problemi idi. Bu görgül

bilimlerin bildirimleri ya da bildirim dizgeleri ile tüm başka

bildirimler — ister dinsel ya da metafiziksel bir karakterde olsunlar,

iserse yalnızca yalancı-bilimsel — arasına (yapılabildiği ölçüde)

bir çizgi çekme problemi idi. Yıllar sonra — 1928 ya da 1929’da

olmuş olmalıdır — bu ilk problemimi ‘‘sınır çekme problemi’’

olarak adlandırdım. Yanlışlanabilirlik ölçütü bu sınır çekme problemine

bir çözümdür, çünkü bildirimlerin ya da bildirim dizgelerinin,

bilimsel sayılabilmek için, olanaklı — ya da tasarlanabilir

— gözlemlerle çatışmaya yetenekli olmaları gerektiğini söyler.

|

Thus the problem which I tried to solve by proposing

the criterion of falsifiability was neither a problem of meaningfulness

or significance, nor a problem of truth or acceptability. It

was the problem of drawing a line (as well as this can be done)

between the statements, or systems of statements, of the empirical

sciences,—and all other statements—whether they are of a religious

or of a metaphysical character, or simply pseudo-scientific.

Years later—it must have been in 1928 or 1929—I called this

first problem of mine the ‘‘problem of demarcation.’’

The criterion of falsifiability is a solution to this problem

of demarcation, for it says that statements or systems of statements,

in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting

with possible, or conceivable, observations. |

III

Bugün hiç kuşkusuz bu sınır çekme ölçütünün — sınanabilirlik

ya da yanlışlanabilirlik ya da çürütülebilirlik ölçütünün —

açık olmaktan uzak olduğunu biliyorum; çünkü şimdi bile imlemi

seyrek olarak anlaşılır. O sıralar, 1920’de, bana hemen hemen

önemsiz görünmüştü, gerçi benim için beni derinden endişelendiren

ve açık kılgısal sonuçları da olan (örneğin politik sonuçlar)

bir entellektüel problemi çözmüş olsa da. Ama henüz tüm imlemlerini

ya da felsefi önemini anlamamıştım. Onu Matematik Bölümünden

tanıdığım bir öğrenciye (şimdi İngiltere’de seçkin bir matematikçi)

açıkladığı zaman, onu yayımlamamı önerdi. O sıralar bunun saçma

olduğunu düşündüm; çünkü problemimin, benim için çok önemli olduğuna

göre, hiç kuşkusuz benim oldukça açık sonucuma ulaşmış olacak

birçok bilimci ve felsefeciyi uyarmış olması gerektiğine inanıyordum.

Durumun bu olmadığını Wittgenstein’ın çalışmasından ve gördüğü

kabulden öğrendim; ve böylece sonuçlarımı on üç yıl sonra Wittgenstein’ın anlamlılık ölçütünün bir eleştirisi biçiminde yayımladım. |

III

Today I know, of course, that this criterion of demarcation — the criterion of testability, or falsifiability, or

refutability — is far from obvious; for even now its significance

is seldom realized. At that time, in 1920, it seemed to me

almost trivial, although it solved for me an intellectual

problem which had worried me deeply, and one which also had

obvious practical consequences (for example, political ones).

But I did not yet realize its full implications, or its philosophical

significance. When I explained it to a fellow student of the

Mathematics Department (now a distinguished mathematician

in Great Britain), he suggested that I should publish it.

At the time I thought this absurd; for I was convinced that

my problem, since it was so important for me, must have agitated

many scientists and philosophers who would surely have reached

my rather obvious solution. That this was not the case I learnt

from Wittgenstein’s work, and from its reception; and so I

published my result thirteen years later in the form of a

criticism of Wittgenstein’s criterion of meaningfulness. |

| Wittgenstein, hepinizin bildiği gibi, Tractatus’ta

(örneğin, bkz. önerme 6.53; 6.54 ve 5) tüm sözde felsefi ya

da metafiziksel önermelerin gerçekte önerme olmadıklarını ya

da yalancı-önermeler olduklarını, anlamsız olduklarını göstermeye

çalıştı. Tüm gerçek (ya da anlamlı) önermeler ‘‘atomik olgu’’ları,

e.d. ilkede gözlem tarafından saptanabilen olguları betimleyen

öğesel ya da atomik önermelerin doğruluk işlevleri idiler. Başka

bir deyişle, anlamlı önermeler işlerin olanaklı durumlarını

betimleyen ve ilkede gözlem tarafından doğrulanabilen ya da

yadsınabilen yalın bildirimler olan öğesel ya da atomik önermelere

tam olarak indirgenebilir idiler. Eğer bir bildirime yalnızca

edimsel bir gözlemi bildirdiği için değil ama ayrıca gözlemlenebilecek herhangi birşeyi bildirdiği için bir ‘‘gözlem bildirimi’’ dersek,

(Tractatus, 5 ve 4.52’ye göre) her doğru önermenin gözlem

bildirimlerinin bir doğruluk-işlevi, ve dolayısıyla onlardan

çıkarsanabilir, olduğunu söylememiz gerekecektir. Tüm öteki

görünürde önermeler anlamsız yalancı-önermeler olacaktır; gerçekte

saçma söz kalabalığından başka birşey olmayacaklardır. |

Wittgenstein as you all know, tried to show in

the Tractatus (see for example his propositions 6.53;

6.54; and 5) that all so-called philosophical or metaphysical

propositions were actually non-propositions or pseudo-propositions:

that they were senseless or meaningless. All genuine (or meaningful)

propositions were truth functions of the elementary or atomic

propositions which described ‘‘atomic facts’’, i.e. — facts

which can in principle be ascertained by observation. In other

words, meaningful propositions were fully reducible to elementary

or atomic propositions which were simple statements describing

possible states of affairs, and which could in principle be

established or rejected by observation. If we call a statement

an ‘‘observation statement’’ not only if it states an actual

observation but also if it states anything that may be

observed, we shall have to say (according to the Tractatus,

5 and 4.52) that every genuine proposition must be a truth-function

of, and therefore deducible from, observation statements. All

other apparent propositions will be meaningless pseudo-propositions;

in fact they will be nothing but nonsensical gibberish. |

Bu düşünce Wittgenstein tarafından felsefeye karşıt

olarak bilimi karakterize etmek için kullanıldı. Örneğin doğal bilimi

felsefe ile karşıtlık içinde duruyor olarak alan 4.11’de şunları

okuruz: ‘‘Doğru önermeler toplamı bütünsel doğal bilimdir (ya

da doğal bilimlerin bütünlüğüdür).’’ Bu demektir ki bilime ait

olan önermeler doğru gözlem bildirimlerinden çıkarsanabilir

olan önermelerdir; bunlar doğru gözlem bildirimleri tarafından doğrulanabilen önermelerdir. Tüm doğru gözlem bildirimlerini

bilebilseydik, doğal bilim tarafından ileri sürülebilecek herşeyi

biliyor da olurduk.

|

This idea was used by Wittgenstein for a characterization

of science, as opposed to philosophy. We read (for example in

4.11, where natural science is taken to stand in opposition

to philosophy): ‘‘The totality of true propositions is the total

natural science (or the totality of the natural sciences).’’

This means that the propositions which belong to science are

those deducible from true observation statements; they

are those propositions which can be verified by true

observation statements. Could we know all true observation statements,

we should also know all that may be asserted by natural science. |

| Bu kaba bir sınır çekme doğrulanabilirlik

ölçütüne varır. Bunu biraz daha az kaba yapmak için, şöyle

iyileştirilebilirdi: ‘‘Bilim alanı içerisine düşmeleri olanaklı

bildirimler gözlem bildirimleri tarafından doğrulanmaları olanaklı

olanlardır; ve bu bildirimler, yine, tüm doğru ya da

anlamlı bildirimler sınıfı ile çakışır.’’ Bu yaklaşım için,

o zaman, doğrulanabilirlik, anlamlılık ve bilimsellik tümü

de çakışır. |

This amounts to a crude verifiability criterion

of demarcation. To make it slightly less crude, it could be

amended thus: ‘‘The statements which may possibly fall within

the province of science are those which may possibly be verified

by observation statements; and these statements, again, coincide

with the class of all genuine or meaningful statements.’’

For this approach, then, verifiability, meaningfulness, and

scientific character all coincide. |

| Ben kişisel olarak sözde anlam problemi ile hiçbir

zaman ilgilenmedim; tersine, bu bana sözel bir problem olarak,

tipik bir yalancı-problem olarak göründü. Yalnızca sınır çekme problemi

ile, e.d. kuramların bilimsel karakterinin bir ölçütünü bulmakla

ilgilendim. Yalnızca bu ilgi idi ki beni hemen Wittgenstein’ın

anlam doğrulanabilirlik ölçütünün bir sınır çekme ölçütü rolünü

de oynamak için amaçlandığını, ve, kuşkulu anlam kavramı konusundaki

tüm endişeler bir yana bırakılsa bile, böyle olarak, bütünüyle

yetersiz olduğunu görmeye götürdü. Çünkü Wittgenstein’ın sınır çekme ölçütü—bu bağlamda kendi terminolojimi kullanırsam—doğrulanabilirlik,

ya da gözlem bildirimlerinden çıkarsanabilirliktir. Ama bu ölçüt

çok fazla dardır (ve çok fazla geniştir): bilimden aşağı

yukarı gerçekte onun karakteristiği olan herşeyi dışlar (ve bu arada

gerçekte astrolojiyi dışlamayı başaramaz). Hiçbir bilimsel kuram

hiçbir zaman gözlem bildirimlerinden çıkarsanamaz, ya da gözlem

bildirimlerinin doğruluk-işlevi olarak betimlenemez. |

I personally was never interested in the so-called

problem of meaning; on the contrary, it appeared to me a verbal

problem, a typical pseudo-problem. I was interested only in

the problem of demarcation, i.e. in finding a criterion of the

scientific character of theories. It was just this interest

which made me see at once that Wittgenstein’s verifiability

criterion of meaning was intended to play the part of a criterion

of demarcation as well; and which made me see that, as such,

it was totally inadequate, even if all misgivings about the

dubious concept of meaning were set aside. For Wittgenstein’s

criterion of demarcation—to use my own terminology in this context—is

verifiability, or deducibility from observation statements.

But this criterion is too narrow (and too wide): it excludes

from science practically everything that is, in fact, characteristic

of it (while failing in effect to exclude astrology). No scientific

theory can ever be deduced from observation statements, or be

described as a truth-function of observation statements. |

Tüm bunları çeşitli vesileler ile Wittgensteincılara ve Viyana Çevresinin üyelerine gösterdim.

1931-2’de düşüncelerimi büyükçe bir kitapta özetledim (Çevrenin

birçok üyesi tarafından okunan bu kitap yayımlanmadı;

ama bir bölümü Bilimsel Keşfin Mantığı başlıklı çalışmama

katıldı); ve 1931’de Erkenntnis’in Yayımcısına yönelik bir

mektup yayımlayarak bunda sınır çekme ve tümevarım problemleri üzerine düşüncelerimi iki sayfaya sıkıştırmaya çalıştım.5 Bu mektupta ve başka yerlerde anlam problemini sınır çekme problemi ile karşıtlık içinde bir yalancı-problem olarak betimledim.

Ama katkım Çevrenin üyeleri tarafından anlam doğrulanabililik

ölçütünü bir anlam yanlışlanabilirlik ölçütü ile değiştirme

yönünde bir önerge olarak sınıflandırıldı — ki gerçekte görüşlerimi

saçmalaştırdı.6 Onların anlam üzerine yalancı-problemlerini değil ama sınır çekme problemini çözmeye çalıştığım yolundaki

protestolarımın hiçbir yararı olmadı.

5Burada genellikle B.K.M. olarak göndermede

bulunulan Bilimsel Keşfin Mantığı (1959, 1960, 1961)

başlıklı çalışmam, bir dizi ek not ve aralarında (s. 312-4’te)

ilkin Erkenntnis’te, 3, 1933, s. 426 vs., yayımlanan

ve burada metinde sözü edilen Erkenntnis’in Yayımcısına

mektup da olmak üzere ekler ile birlikte, Logik der Forschung’un

çevirisidir.

Burada metinde sözü edilen ve hiçbir zaman yayımlanmayan kitabım

konusunda Carnap’ın ‘‘Über Protokolsätze’’ (Protokol-Tümceler

Üzerine) başlıklı denemesine bakınız, Erkenntnis,

3, 1932, s. 215-28. Bunda s. 223-8’de Carnap kuramımın bir

taslağını verir, ve onu kabul eder. Kuramımı ‘‘yordam B’’

olarak adlandırır, ve (s. 224 üstte) der ki: ‘‘Neurath’ınkinden’’

(ki s. 223’te Carnap’ın ‘‘yordam A’’ dediği şeyi geliştirmiştir)

‘‘ayrı bir bakış açısından yola çıkarak, Popper dizgesinin

parçası olarak yordam B’yi geliştirdi.’’ Ve sınamalar kuramımı

ayrıntıda betimledikten sonra, Carnap kendi görüşlerini şöyle

toparlar (s. 228): ‘‘Burada tartışılan değişik uslamlamaları

tarttıktan sonra, bana öyle görünüyor ki yordam B—burada betimlenen

biçimde—günümüzde ... bilgi kuramında ... savunulan bilimsel

dil biçimleri arasında en yeterli olanıdır.’’ Carnap’ın bu

denemesi benim eleştirel sınama kuramımın yayımlanan ilk raporunu

kapsıyordu. (Bkz. ayrıca B.K.M.’deki eleştirel gözlemlerim,

Kesim 29’a not 1, s. 104; ‘‘1933’’ tarihi ‘‘1932’’ olarak

okunmalıdır; ve aşağıda Bölüm 11, Not 39 için metin.)

6Wittgenstein’ın anlamsız bir yalancı-önerme örneği

şudur: ‘‘Sokrates özdeştir.’’ Açıktır ki ‘‘Sokrates özdeş

değildir’’ de saçma olmalıdır. Böylece herhangi bir saçmanın

olumsuzlanması saçma, ve anlamlı bir bildiriminki anlamlı

olacaktır. Ama sınanabilir (ya da yanlışlanabilir) bir bildirimin olumsuzlanmasının sınanabilir olması gerekmez,

ilkin B.K.M.’da (örneğin s. 38 vs) ve daha sonra eleştirmenlerim

tarafından belirtildiği gibi. Sınanabilirliği bir sınır çekme ölçütü olarak değil de bir anlam ölçütü olarak almanın

yarattığı karışıklık kolayca göz önüne getirilebilir. |

All this I pointed out on various occasions to Wittgenstenians

and members of the Vienna Circle. In 1931-2 I summarized my

ideas in a largish book (read by several members of the Circle

but never published; although parts of it was incorporated

in my Logic of Scientific Discovery); and in 1933 I

published a letter to the Editor of Erkenntnis in which

I tried to compress into two pages my ideas on the problems

of demarcation and induction.5 In this letter and

elsewhere I described the problem of meaning as a pseudo-problem,

in contrast to the problem of demarcation. But my contribution

was classified by members of the Circle as a proposal to replace

the verifiability criterion of meaning by a falsifiability

criterion of meaning — which effectively made non-sense

of my views.6 My protests that I was trying to

solve, not their pseudo-problem of meaning, but the problem

of demarcation, were of no avail.

5My Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959,

1960, 1961), here usually referred to as L.Sc.D., is

the translation of Logik der Forschung (1934), with

a number of additional notes and appendices, including (on

pp. 312-14) the letter to the Editor of Erkenntnis mentioned here in the text which was first published in Erkenntnis,

3, 1933, pp. 426 f.

Concerning my never published book mentioned here in the text,

see R. Carnap’s paper ‘‘Über Protokollstäze’’ (On Protocol-Sentences), Erkenntnis, 3, 1932, pp. 215-28 where he gives an outline

of my theory on pp. 223-8, and accepts it. He calls my theory

‘‘procedure B,’’ and says (p. 224, top): ‘‘Starting from a

point of view different from Neurath’s’’ (who developed what

Carnap calls on p. 223 ‘‘procedure A’’), ‘‘Popper developed

procedure B as part of his system.’’ And after describing

in detail my theory of tests, Carnap sums up his views as

follows (p. 228): ‘‘After weighing the various arguments here

discussed, it appears to me that the second language form

with procedure B—that is in the form here described—is the

most adequate among the forms of scientific language at present

advocated ... in the ... theory of knowledge.’’ This paper

of Carnap’s contained the first published report of my theory

of critical testing. (See also my critical remarks in L.Sc.D.,

note 1 to section 29, p. 104, where the date ‘‘1933’’ should

read ‘‘1932’’; and ch. 11, below, text to note 39.)

6Wittgenstein’s example of a nonsensical pseudo-proposition

is: ‘‘Socrates is identical.’’ Obviously, ‘‘Socrates is not

identical’’ must also be nonsense. Thus the negation of any

nonsense will be nonsense, and that of a meaningful statement

will be meaningful. But the negation of a testable (or

falsifiable) statement need not be testable, as was pointed

out, first in my L.Sc.D. (e.g. pp. 38 f.) and later

by my critics. The confusion caused by taking testability

as a criterion of meaning rather than of demarcation can easily be imagined. |

Bununla birlikte doğrulama üzerine saldırılarımın biraz etkisi

oldu. Çok geçmeden doğrulamacı anlam ve anlamsız felsefecilerinin

kampında tam bir karışıklığa götürdü. Anlam ölçütü olarak

başlangıçtaki doğrulanabilirlik önergesi en azından duru,

yalın ve güçlü idi. Şimdi getirilen değişkiler ve kaymalar

tam tersiydiler.7 Belirtmem gerek ki bu şimdi katılanlar tarafından bile anlaşılmıştır. Ama benden genellikle onlardan

biri olarak söz edildiği için, bu karışıklığı yaratmış olmama

karşın hiçbir zaman ona katılmadığımı yinelemek istiyorum.

Ne yanlışlanabilirlik ne de sınanabilirlik bir anlam ölçütü

olarak benim tarafımdan önerilmiş değildir; ve gerçi her iki

terimi de tartışmaya getirme konusundaki suçumu kabul etsem

de, onları anlam kuramına getiren ben değildim.

Benim olduğu söylenen görüşlerin eleştirisi yaygın ve oldukça

başarılıdır. Gene de henüz görüşlerimin bir eleştirisi ile

karşılaşabilmiş değilim.8 Bu arada, sınanabilirlik

bir sınır çekme ölçütü olarak yaygın olarak kabul edilmektedir.

7Bu problemin tarihinin nasıl yanlış anlaşıldığını

gösteren en yakın örnek A. R. White’ın ‘‘Note on Meaning and

Verification’’dur [‘‘Anlam ve Doğrulama Üzerine Not’’], Mind,

62, 1954, s. 66 vs. J. L. Evans’ın Mr. White tarafından eleştirilen

makalesi, Mind, 62, 1953, s. 1 vs, benim görüşümde

çok değerli ve alışılmadık ölçüde kavrayışlıdır. Kolayca anlaşılabilir

ki, yazarlardan hiç biri öyküyü yeniden toparlamada başarılı

değildir. (Kimi ipuçları Açık Toplum başlıklı çalışmamda,

bölüm 11’e not 46, 51 ve 52, bulunabilir; ve daha tam bir

çözümleme bu kitabın 11’inci bölümünde.)

8B.K.M.’nda daha sonra gerçekten de yanıtlarıma

gönderme olmaksızın getirilen kimi olası karşıçıkışları tartıştım

ve yanıtladım. Bunlardan biri doğal bir yasayı yanlışlamanın

tıpkı onu doğrulama denli olanaksız olduğu önesürümüdür. Yanıt

bu karşıçıkışın bütünüyle ayrı olan iki çözümleme düzeyini

karıştırdığıdır (tıpkı matematiksel tanıtların olanaksız olduğu

çünkü sağlamanın, ne denli sık yinelenirse yinelensin, hiçbir

zaman bir yanlışı gözden kaçırmamamızı tam olarak sağlama

bağlayamayacağı karşıçıkışı gibi). Birinci düzeyde, mantıksal

bir bakışımsızlık vardır: tek bir tekil bildirim — diyelim

ki Merkür’ün güneşe en yakın yörünge noktasına ilişkin — biçimsel

olarak Kepler’in yasalarını yanlışlayabilir; ama bunlar herhangi

bir sayıda tekil bildirimler tarafından biçimsel olarak doğrulanamazlar.

Bu bakışımsızlığı önemsizleştirme girişimi ancak karışıklığa

götürebilir. Bir başka düzlemde, herhangi bir bildirimi, giderek

en yalın gözlem bildirimini bile kabul etmede duraksayabiliriz;

ve her bildirimin kuramlar ışığında yorum içerdiğini

ve dolayısıyla belirsiz olduğunu belirtebiliriz. Bu temel

bakışımsızlığı etkilemez, ama önemlidir: yüreğin Harvey’den

önceki kesimleyicilerinden çoğu yanlış şeyler gözlemlediler—görmeyi

bekliklerini. Hiçbir zaman yanlış yorumlama tehlikelerinden

özgür, emin bir gözlem diye birşey olamaz. (Bu tümevarım kuramının

işlememesinin nedenlerinden biridir.) ‘‘Görgül temel’’ büyük

ölçüde (‘‘yeniden-üretilebilir etkiler’’in) alt düzey evrensellik kuramlarının bir karışımından oluşur. Ama, araştırmacının

(riski göze alarak) kabul edebileceği herhangi bir temel ile

göreli olarak, araştırmacı kuramını ancak onu çürütmeye çalışarak

sınayabilir. |

My attacks upon verification had some effect, however. They

soon led to complete confusion in the camp of the verificationist

philosophers of sense and nonsense. The original proposal

of verifiability as the criterion of meaning was at least

clear simple, and forceful. The modifications and shifts which

were now introduced were the very opposite.7 This,

I should say, is now seen even by the participants. But since

I am usually quoted as one of them I wish to repeat that although

I created this confusion I never participated in it. Neither

falsifiability nor testability were proposed by me as criteria

of meaning; and although I may plead guilty to having introduced

both terms into the discussion, it was not I who introduced

them into the theory of meaning. Criticism of my alleged views

was widespread and highly successful. I have yet to meet a

criticism of my views.8 Meanwhile, testability

is being widely accepted as a criterion of demarcation.

7The most recent example of the way in which the

history of this problem is misunderstood is A. R. White’s

‘‘Note on Meaning and Verification,’’ Mind, 63, 1954,

pp. 66 ff. J. L. Evan’s article, Mind, 62, 1953, pp.

1 ff., which Mr. White criticizes, is excellent in my opinion,

and unusually perceptive. Understandably enough, neither of

the authors can quite reconstruct the story. (Some hints may

be found in my Open Society, notes 46, 51 and 52 to

ch. 11; and a fuller analysis in ch. 11 of the present volume.)

8In L.Sc.D. I discussed, and replied to,

some likely objections which afterwards were indeed raised,

without reference to my replies. One of them is the contention

that the falsification of a natural law is just as impossible

as its verification. The answer is that this objection mixes

two entirely different levels of analysis (like the objection

that mathematical demonstrations are impossible since checking,

no matter how often repeated, can never make it quite certain

that we have not overlooked a mistake). On the first level,

there is a logical asymmetry: one singular statement — say

about the perihelion of Mercury — can formally falsify Kepler’s

laws; but these cannot be formally verified by any number

of singular statements. The attempts to minimize this asymmetry

can only lead to confusion. On another level, we may hesitate

to accept any statement, even the simplest observation statement;

and we may point out that every statement involves interpretation

in the light of theories, and that it is therefore uncertain.

This does not affect the fundamental asymmetry, but it is

important: most dissectors of the heart before Harvey observed

the wrong things — those, which they expected to see. There

can never be anything like a completely cafe observation,

free from the dangers of misinterpretation. (This is one of

the reasons why the theory of induction does not work.) The

‘‘empirical basis’’ consists largely of a mixture of theories of lower degree of universality (of ‘‘reproducible effects’’).

But the fact remains that relative to whatever basis the investigator

may accept (at his peril), he can test his theory only be

trying to refute it. |

|

IV

Sınır çekme problemini biraz ayrıntılı olarak tartıştım çünkü

inanıyorum ki çözümü bilim felsefesinin temel problemlerinden

çoğunun çözümüne anahtardır. Sizlere daha sonra bu öteki problemlerin

bir listesini vereceğim, ama bunlardan yalnızca biri — tümevarım

problemi — burada biraz uzunlamasına tartışılabilir. |

IV

I have discussed the problem of demarcation in some detail

because I believe that its solution is the key to most of

the fundamental problems of the philosophy of science. I

am going to give you later a list of some of these other

problems, but only one of them — the problem of induction — can be discussed here at any length. |

| Tümevarım problemi ile 1923’te ilgilenmeye başlamıştım.

Gerçi bu problem sınır çekme problemi ile çok yakından ilgili olsa

da, bağlantıyı yaklaşık beş yıl gibi bir süre boyunca tam olarak

kavrayamadım. |

I had become interested in the problem of induction

in 1923. Although this problem is very closely connected with

the problem of demarcation, I did not fully appreciate the connection

for about five years. |

Tümevarım problemine Hume yoluyla yaklaştım. Hume, sanırım,

tümevarımın mantıksal olarak aklanamayacağını göstermede bütünüyle

haklıydı. ‘‘Hiçbir deneyimlerini edinmediğimiz durumlar

deneyimlerini edindiklerimizi andırır’’ görüşünü doğrulamak

için geçerli hiçbir mantıksal9 uslamlama olamayacağını

savundu. Buna göre ‘‘nesnelerin sık ya da değişmez birlikteliğinin

gözleminden sonra bile, herhangi bir nesne üzerine deneyimlerini

edinmiş olduklarımızın ötesinde herhangi bir çıkarsamada bulunmak

için hiçbir nedenimiz yoktur.’’ Çünkü ‘‘eğer deneyimizin

olduğu söylenirse,’’10 — deneyim bize sürekli

olarak belli başka nesneler ile birlikte bulunan nesnelerin

böyle birlikte olarak sürdüklerini öğrettiği için — o zaman,

der Hume, ‘‘sorumu yineleyeceğim, niçin bu deneyimden deneyimlerini

edinmiş olduğumuz geçmiş durumların ötesinde herhangi bir

vargı oluştururuz?’’ Başka bir deyişle, deneyime bir başvuru

ile tümevarım uygulamasını aklama yönünde bir girişim bir sonsuz gerilemeye götürmelidir. Bir sonuç olarak diyebiliriz

ki kuramlar hiçbir zaman gözlem bildirimlerinden çıkarsanamaz

ya da onlar tarafından ussal olarak aklanamazlar.

10Bu ve sonraki alıntı aynı yer, kesim vi’dendir.

Bkz. ayrıca Hume, Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding,

kesim iv, Bölüm II; ve 1938’de J. M. Keynes ve P. Sraffa tarafından

yayıma hazırlanan, ve B.K.M.’nda yeni ek vii, not 6’ya

metinde alıntılanan Özet’i. |

I approached the problem of induction through Hume. Hume,

I felt, was perfectly right in pointing out that induction

cannot be logically justified. He held that there can be no

valid logical9 arguments allowing us to establish

‘‘that those instances, of which we have had no experience,

resemble those, of which we have had experience.’’ Consequently

‘‘even after the observation of the frequent or constant

conjunction of objects, we have no reason to draw any inference

concerning any object beyond those of which we have had experience.’’

For ‘‘shou’d it be said that we have experience’’10 — experience teaching us that objects constantly conjoined

with certain other objects continue to be so conjoined — then,

Hume says, ‘‘I wou’d renew my question, why from this experience

we form any conclusion beyond those past instances, of which

we have had experience.’’ In other words, an attempt to

justify the practice of induction by an appeal to experience

must lead to an infinite regress. As a result we can

say that theories can never be inferred from observation statements,

or rationally justified by them.

10This and the next quotation are from loc.

cit., section vi. See also Hume’s Enquiry Concerning

Human Understanding, section IV, Part II, and his Abstract, edited 1938 by J. M. Keynes and P. Sraffa, p. 15, and

quoted in L.Sc.D., new appendix VII, text to note 6. |

| Hume’un tümevarımcı çıkarsamayı çürütmesini duru

ve belirleyici buldum. Ama çıkarsamayı alışkanlık terimlerinde

ruhbilimsel açıklamasını doyurucu olmaktan bütünüyle uzak buldum.

Sık sık Hume’un bu açıklamasının felsefi olarak çok doyurucu

olmadığı belirtilmiştir. Bununla birlikte, hiç kuşkusuz felsefi

olmaktan çok ruhbilimsel bir kuram olarak amaçlanmıştır;

çünkü ruhbilimsel bir olgunun — kurallılıkları ya da sürekli

olarak birlikte bulunan türde olayları önesüren bildirimlere,

e.d. yasalara inanmamız olgusunun — alışkanlığa bağlı

olduğunu (e.d. sürekli olarak onunla birlikte bulunduğunu) ileri

sürerek nedensel bir açıklamasını vermeye çalışır. Ama Hume’un

kuramının bu yeniden-formülasyonu bile henüz doyurucu değildir;

çünkü şimdi bir ‘‘ruhbilimsel olgu’’ dediğim şeyin kendisi bir

alışkanlık — yasalara ya da kurallılıklara inanma alışkanlığı

— olarak betimlenebilir; ve böyle bir alışkanlığın bir alışkanlığa

(üstelik ayrı bir alışkanlık olsa bile) bağlı ya da onunla birlikte

bulunuyor olarak açıklanması gerektiğini duymak ne çok şaşırtıcı

ne de çok aydınlatıcıdır. Ancak ‘‘alışkanlık’’ sözcüğünün Hume

tarafından sıradan dilde olduğu gibi yalnızca kurallı davranışı betimlemek için değil ama dahaçok (sık yinelemeye yüklenen) kökeni konusunda kuram üretmek için kullanıldığını anımsadığımız

zaman, onun ruhbilimsel kuramını daha doyurucu bir yolda yeniden-formüle

edebiliriz. O zaman diyebiliriz ki, başka alışkanlıklar gibi, yasalara inanma alışkanlığımız sık yinelemenin — belli

bir türde şeylerin sürekli olarak bir başka türden şeyler ile

birlikte oldukları üzerine yineleyen gözlemin — ürünüdür. |

I found Hume’s refutation of inductive inference

clear and conclusive. But I felt completely dissatisfied with

his psychological explanation of induction in terms of custom

or habit.

It has often been noticed that this explanation of Hume’s is

philosophically not very satisfactory. It is, however, without

doubt intended as a psychological rather than a philosophical

theory; for it tries to give a causal explanation of a psychological

fact — the fact that we believe in laws, in statements

asserting regularities or constantly conjoined kinds of events

— by asserting that this fact is due to (i.e. constantly conjoined

with) custom or habit. But even this reformulation of Hume’s

theory is still unsatisfactory; for what I have just called

a ‘‘psychological fact’’ may itself be described as a custom

or habit — the custom or habit of believing in laws or regularities;

and it is neither very surprising nor very enlightening to hear

that such a custom or habit must be explained as due to, or

conjoined with, a custom or habit (even though a different one).

Only when we remember that the words ‘‘custom’’ and ‘‘habit’’

are used by Hume, as they are in ordinary language, not merely

to describe regular behaviour, but rather to theorize

about its origin (ascribed to frequent repetition), can

we reformulate his psychological theory in a more satisfactory

way. We can then say that, like other habits, our habit of

believing in laws is the product of frequent repetition —

of the repeated observation that things of a certain kind are

constantly conjoined with things of another kind. |

| Bu türeyişsel-ruhbilimsel kuram, belirtildiği gibi,

sıradan dile katılmıştır, ve dolayısıyla Hume’un düşündüğü gibi

devrimci olmaktan çok uzaktır. Hiç kuşkusuz aşırı ölçüde popüler

bir ruhbilimsel kuram, deyim yerindeyse, ‘‘sağ duyu’’nun bir

parçasıdır. Ama hem sağ duyuya hem de Hume’a duyduğum sevgiye

karşın, bu ruhbilimsel kuramın yanlış olduğu, ve gerçekte salt

mantıksal zeminde çürütülebilir olduğu kanısına vardım. |

This genetico-psychological theory is, as indicated,

incorporated in ordinary language, and it is therefore hardly

as revolutionary as Hume thought. It is no doubt an extremely

popular psychological theory — part of ‘‘common sense,’’ one

might say. But in spite of my love of both common sense and

Hume, I felt convinced that this psychological theory was mistaken;

and that it was in fact refutable on purely logical grounds. |

Hume’un ruhbilimi—ki popüler ruhbilimdir — sanırım

en azından üç ayrı şeyde yanılıyordu: (a) yinelemenin

tipik sonucu; (b) alışkanlığın doğuşu; (c) ‘‘bir

yasaya inanma’’ ya da ‘‘olayların yasa-benzeri bir ardışıklığını

bekleme’’ olarak betimlenebilecek deneyimlerin ya da davranış

kiplerinin karakteri.

|

Hume’s psychology, which is the popular psychology,

was mistaken, I felt, about at least three different things:

(a) the typical result of repetition; (b) the

genesis of habits; and especially (c) the character of

those experiences or modes of behaviour which may be described

as ‘‘believing in a law’’ or ‘‘expecting a law-like succession

of events.’’ |

| (a) Yinelemenin — diyelim ki, piyanoda

güç bir pasajı yinelemenin — tipik sonucu ilkin dikkat gerektiren

devimlerin sonunda dikkat olmaksızın yerine getirilmesidir.

Diyebiliriz ki süreç kökten kısaltılır ve bilinçli olmaya son

verir: ‘‘ruhbilimsel’’ olur. Böyle bir süreç, bilinçli bir yasa-benzeri

ardışıklık beklentisi, ya da yasaya bir inanç yaratmaktan uzak,

tersine bilinçli bir inanç ile başlayabilir ve onu gereksizleştirerek

yok edebilir. Bisiklete binmeyi öğrenmede eğer dümeni düşme tehlikesinde

olduğumuz yöne kırarsak düşmekten kaçınabileceğimiz inancı ile

başlayabiliriz, ve bu inanç devimlerimizi gütmede yararlı olabilir.

Yeterli alıştırmadan sonra kuralı unutabiliriz; her ne olursa

olsun, bundan böyle ona gereksinmeyiz. Öte yandan, yinelemenin

bilinçsiz beklentiler yaratabileceği doğru olsa bile, bunlar

ancak birşey ters giderse bilinçli olurlar (saatin vurduğunu

duymayabilir, ama durduktan sonra onu duyabiliriz). |

(a) The typical result of repetition —

say, of repeating a difficult passage on the piano — is that

movements which at first needed attention are in the end executed

without attention. We might say that the process becomes radically

abbreviated, and cease to be conscious: it becomes ‘‘physiological.’’

Such a process, far from creating a conscious expectation of

law-like succession, or a belief in a law, may on the contrary

begin with a conscious belief and destroy it by making it superfluous.

In learning to ride a bicycle we may start with the belief that

we can avoid falling if we steer in the direction in which we

threaten to fall, and this belief may be useful for guiding

our movements. After sufficient practice we may forget the rule;

in any case, we do not need it any longer. On the other hand,

even if it is true that repetition may create unconscious expectations,

these become conscious only if something goes wrong (we may

not have heard the clock tick, but we may hear that it has stopped). |

| (b) Alışkanlıklar, bir kural olarak, yinelemeden köken almazlar. Giderek yürüme, konuşma, belli saatlerde

beslenme alışkanlığı bile yineleme ne olursa olsun herhangi

bir rol oynamadan önce başlar. Eğer dilersek diyebiliriz

ki, bunlar ancak yineleme tipik rolünü oynadıktan sonra ‘‘alışkanlıklar’’

olarak adlandırılmayı hak ederler; ama söz konusu alıştırmaların

birçok yinelemenin sonucu olarak köken aldıklarını söylememeliyiz. |

(b) Habits or customs do not, as a rule, originate in repetition. Even the habit of walking, or

of speaking, or of feeding at certain hours, begin before

repetition can play any part whatever. We may say, if we like,

that they deserve to be called ‘‘habits’’ or ‘‘customs’’ only

after repetition has played its typical part; but we must not

say that the practices in question originated as the result

of many repetitions. |

(c) Bir yasaya inanç olayların yasa-benzeri bir ardışıklığı

beklentisini ele veren bir davranış ile bütünüyle aynı şey